© Meera Varma

Conversations about mental health are more important than ever, yet the stigma surrounding it prevails. Meera Varma is fighting to normalise therapy, mental health support, and education.

Not many people at the tender age of 22 can say they’ve been invited to the White House in Washington DC alongside actress and singer Selena Gomez to speak to the President of the United States and the First Lady. Meera Varma, mental health activist, and UCLA University graduate, and current UCLA graduate student, has done just that.

Talking to one of the most powerful political leaders in the world about mental health was an important milestone in her activism, and mental health education is close to her heart and something she deeply relates to. Aged only 14, Meera experienced a decline in her own mental health that nearly saw her end her own life aged 17. Although she credits her family and teachers at high school for supporting her through this challenging time, she noticed that mental health resources were either insufficient or non-existent.

Since then, Meera has worked and advocated tirelessly for important and permanent changes to be made, not just in her own school and her university but in the education system on a national level. Her activism asks educators to include resources on mental health in the curriculum and school policies and that people can ask for a mental health day separately from a sick day.

Having recently become Impact’s Mental Health Writer and due to give a TED Talk at UCLA this June, Meera Varma is paving the way for fundamental change in the perception and treatment of mental health. Amongst a busy schedule, she spoke to INJECTION about her own story and experience, overcoming language barriers, and what motivates her to keep fighting for a new perception of mental health in the 21st century.

Are you able to tell us a little about your own experiences with mental health?

Looking back, I was probably struggling with my mental health from when I was 10 or 11 years old. I didn't know it back then, my family didn't know it back then, we all thought: It’s normal, she’s going through puberty. But as I got older, in middle school and in high school, that's when I started to experience very, very severe mental health crises. Teachers would have to stop teaching me, and they would have to help me go to the nurse's office. At one point, I just couldn't even go to school, it became so incredibly difficult. I was just not living to thrive, but living to literally just survive.

It was very difficult because, growing up as an Asian Indian woman, mental health is not talked about as openly as I would like. It was difficult to articulate what I was going through and how to explain these changes. However, I am fortunate enough to have parents and a family that has supported me, and I was able to get help for my mental health. And, you know, that comes with a privilege; not a lot of people are able to seek care for their mental health. That is something that is an issue in America. And my hope is that we treat mental health the same as physical health because mental health is a whole part of health.

Just because you're not diagnosed with a mental illness does not make your mental health less valid - we all have mental health that deserves to be taken care of.

When I was 14, I experienced the stigma and shame of having these mental health episodes in school, and I got a lot of judgement. I felt stigmatised by my peers and other people in my school. And I remember wondering: Why, if I had a physical ailment, like, if I walked into a class with a cast on my arm, would I be treated totally differently?

Since then, I started sharing my story. I have spoken on panels, and last year I went to the White House, where I spoke with President Biden and his administration about our mental health crisis and how more things need to be done to prioritise mental health.

Since my time in the White House, I have changed mental health policy on a local level - I worked with my school district as well as UCLA College to have them print the suicide hotline on the back of all student ID cards. I'm just very passionate about sharing my story to not only cultivate more conversation around mental health but to really invoke that systemic change and really push for people in power to be doing more for mental health.

Suicide is the leading cause of death for individuals aged 15 to 25 in the United States, and that is something that can be prevented by having conversations like we are having now. I think it's so important for everyone to be here for each other, to open our ears and really listen and validate each other and what we're going through.

Since then, I started sharing my story. I spoke with my school district, and I've spoken on panels. I've spoken to people in government, advocating for mental health policy. And my activism took me to the White House last year, where I spoke with President Biden and his administration about our mental health crisis and how more things need to be done to prioritise mental health.

You found help through therapy eventually, after not gelling with your first therapist. How did your inner circle of friends react to that?

I always like to preface talking about this by saying how grateful and deeply privileged I am to have been a recipient of therapy. And I hope that one day soon, anyone can get the help they need and deserve. But to answer your question: I think it was five or six therapists I tried before I found one that actually worked for me. I found someone that understood my cultural beliefs because, being an Indian person, it's hard for someone that doesn't understand my culture, to understand the cultural stigma that I faced with mental health services.

I was the first person in my family to go to therapy. I'm the youngest one of my family of four Out of my extended family, I’m the second-oldest grandchild. So you know, it's kind of setting an example for the younger grandchildren.

“Wait, my older cousin is in therapy?” “What do you talk about in therapy?” These were questions that my younger cousins asked me. And I wanted to reframe the conversation into a positive one – therapy is a place where a person can feel validated in their experiences, and having someone to talk to can be a great source of healing. I had those conversations with them to try and change their perception of therapy.

My inner circle, my family, they were supportive of it, even though at first it was like, why can't you talk to us? We're your family! We care about you. We love you. But having a therapist is different. Sometimes it helps to get a third perspective and to have someone with a clinical degree to help you and give you concrete strategies for your problems. When I'm having a negative thought, what can I do to redirect my attention? How can I cope with the intense feelings that I have? It's important that I had that opportunity to learn from a therapist, so I can employ those strategies on my own.

I invited different family members to my therapy sessions as well. I wanted my family to be kept in the loop. I think my family felt a little helpless at first because it's so heartbreaking to see someone you love go through something so challenging and not know how to help. My family took it as a huge learning opportunity for all of us; we can learn how to be here for each other. It really helped them to reframe that it's okay to ask for help.

Another part of my activism is to emphasise that therapy is for everyone. You can get help from a therapist about anything, even if your life is going great. You can ask someone for help, you can just have that space, that opportunity to talk with someone.

© Photography Meera Varma

It’s clear that there is a lot of work to be done for mental health in the world. What, in your opinion, is the biggest roadblock to making permanent changes in favour of mental health policies?

I think one of the biggest roadblocks is the lack of education about mental health and how real and valid it is. There's literal evidence of how the brain chemistry of a person with depression is different from that of a person who is not living with depression. There are powerful images of brain scans and how the levels of brain activity are fundamentally different; you can see the difference in the levels of activity in the brain of someone that has OCD or has an eating disorder or has bipolar disorder, or anxiety.

People need to understand that mental illness might look invisible, AND it's still real. We are trained in how to give CPR, but we are not trained in how to help someone with a panic attack! I have experienced many panic attacks in my life, and no one in my life knew how to help me with them. Why aren't we trained on how to help someone that is going through a depressive episode or that has a lot of anxiety? It's because there's a lack of education around it. And if you see something that is unfamiliar to you, you're more likely to judge it.

You mention that it was difficult for you to explain mental health to your family in the Hindi language. In your experience, are there other languages that can’t express the ins and outs of mental health, and how do you think this problem can be solved?

I love talking about this because it's so important to make the conversation of mental health intersectional. Everyone has mental health, regardless of culture, background, and language, and I think it's important to talk about this with my personal experience.

My grandparents' first language was not English. And they are my biggest support system for my own mental health. So trying to explain my mental health challenges or even how depression works or how medication works was very difficult to explain because there's no word for ‘stigma’ in Hindi. So I distinctly remember showing them videos on YouTube, explaining it through animation videos from TED-Ed, and I'll put the subtitles in Hindi so they could read it. Having them read the video in their native language totally changed the game for them because it felt like it was more relatable. It felt like someone was speaking to them from their culture, and it made them feel more included in the conversation.

And since then, it's just incredible seeing how much their view on mental health has changed. They take care of their own mental health, and they talk about mental health with their Indian senior citizen group. I think it has just been such a positive snowball effect. They talk to their friends about mental health. They are just incredible. And I would not be here, like where I am today, without them.

I don't want to generalise because each culture is so unique and different and beautiful. My personal experience is from talking to my friends from other cultures who have experienced a similar thing. We found that once you see someone struggling, someone, you love and care about, it makes you more willing to learn about it and to change your attitude about it because it's personal to you. Talking about mental health and making it a more intersectional conversation is so important.

© Photography Meera Varma

How do you motivate yourself when things get tough during your work?

I think of what 10 or 11-year-old Meera would have wanted and needed back then. At one point, I did not think I would make it to 18. And now I'm 22. So a lot of the work I do, I just think of the younger me, and I think of all of the people that have been in my shoes, who are in my shoes, and the people that aren't here with us anymore. I hold that very deeply in my heart. Mental health doesn't discriminate. We all experience mental health challenges in our entire life, throughout our life.

My activism is my purpose, that's why I'm here. That's a lot of what keeps me going; knowing that I changed people's lives is surreal to me.

I want to work towards a future where future generations don't have to worry and feel scared of talking about mental health.

What has been a highlight of your activism so far?

I'm so excited to talk to you about something in this interview that happened only recently! I recently got accepted to give a TED talk at UCLA. I will be sharing the importance of having mental health conversations. I think that has been very career-affirming to me.

I think another career-affirming experience for me has been having my voice heard at the White House by President Biden and his administration and showing him my tattoo of the semicolon (a semicolon is symbolic of when someone wanted to end their life but chose to continue). My tattoo is a message that I keep on going and that I am strong. And I showed President Biden – look, this is what it looks like to survive a mental health challenge.

But the biggest highlight has to be just hearing from people that I've touched them in some way or having people value what I do. I did not think my life would lead me here.

© Photography Meera Varma

What would you say to someone who is struggling and can’t see any way out of the darkness?

Being someone that has been in that position, I understand how hard it is to see the light.

I would say:

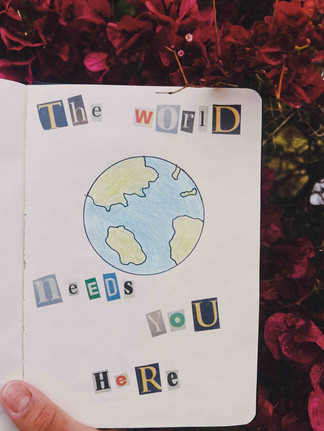

"Thank you for trusting me with your deepest, most intimate feelings. I need you here. The world needs you here. And I know you can't see it right now. I promise you that it is going to get better, and you are not alone. I am here for you. I love you, I care about you. And what you're going through is real. And, you know, it's okay to not be okay."

I would also say that if you know you are struggling, I am here. I want to listen, I want to be here for you. You are not a burden.

As we wrap up the interview, I want to keep talking to Meera and listen to her speak passionately about the importance of mental health. There is warmth, sincerity, and strength in what she says, and you know instantly that she means every single word. Far from being elusive about the impact she already has on those that have had the honour of meeting her and working with her, she remains humbled by her experiences, her connections, and the changes she evokes.

Meera Varma will be synonymous with mental health education and never giving up the fight to make sure that those in the darkest of places have a voice that speaks up for them.

Living with type 2 diabetes is more manageable with jardiance price. Its innovative formula helps reduce blood sugar levels naturally while lowering the risks of heart complications. Patients who use Jardiance report feeling more in control of their health, making it an excellent choice for those seeking a comprehensive treatment solution.